In The Ear Of The Beholders

They are two words in Italian that make some opera lovers swoon and others sneer.

The expression is «bel canto» — translated as beautiful singing — and it generally refers to a style of brilliantly decorative and virtuosic singing in the Italian operas of early 19th-century composers Gaetano Donizetti and Vincenzo Bellini.

Nowadays it seems fashionable for vocal artists to release a CD of bel canto arias. And for certain connoisseurs, a CD collection would be incomplete without several recordings of a single bel canto opera, each sung by a different diva who has put her own distinctive vocal and dramatic signature on a role.

Still, there are many — including more than a few orchestral players — bored by bel canto’s uninteresting accompaniment of mostly chords and arpeggios. Sure, it’s pretty singing, they say, but still lightweight, especially compared to the dramatic heft of Verdi and Puccini or the philosophical and musical weight of Wagner and Strauss.

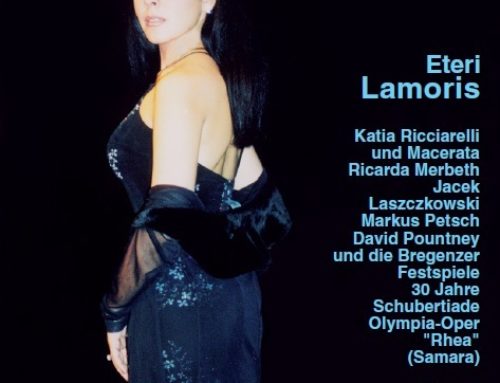

It’s these nonbelievers whom Connecticut Opera artistic director Willie Anthony Waters and soprano Eteri Lamoris hope to win over tonight and Saturday when they perform that quintessential bel canto opera «Lucia di Lammermoor» by Donizetti. (As is tradition for the opera company, the Sunday matinee performance has a different lead, soprano Eglise Gutierrez.)

Based on the Sir Walter Scott novel «The Bride of Lammermoor,» «Lucia» revolves around its tragic protagonist whose unpermitted love (in this case, love for the head of a feuding Scottish clan) seals her fate. All the way through the opera, the lead soprano sings one punishing round of vocal calisthenics after another: runs, roulades, trills, scales and arpeggios. And there’s a climactic mad scene in which the soprano’s tonal palette, or coloratura, increases in proportion to the heightened drama.

But bel canto means more than singing a lot of pretty notes, say Lamoris and Waters.

«For me, what’s important for bel canto is not just singing beautifully but singing expressively so that the words and the music mean something together,» says Lamoris. «For the first time in my life, I understood the real meaning of bel canto when I sang Lucia, and for me it was a wonderful experience.»

Lamoris’ coloratura has also sung in this country with Washington Opera and Pittsburgh Opera.

Waters says he was first taken by Lamoris when she auditioned for him last fall, singing «Una voce poco fa» from Rossini’s «The Barber of Seville.» «Immediately, you knew the personality,» he says. «Not only did she sing it beautifully, but she acted it out, and she was feisty, coy, charming — she was all those things, just in that one aria.»

Lamoris was raised in a family of artists. Her father was a ballet dancer in St. Petersburg, and her mother is a respected opera singer who taught Eteri most of her technique. Her other determining influence was Renata Scotto, the legendary soprano whose dramatic singing, along with Maria Callas and Joan Sutherland, transformed bel canto in the ’50s and ’60s to a much more appreciated art form.

Raised on Scotto’s recordings, Lamoris started taking lessons with her idol after seeing the soprano teach a master class in Vienna.

«She gave a lot to me. Not just technically but also in emotional characters. She always was my example, very big example,» says Lamoris. «When I first heard her, I felt something common in her emotionally, her and me.»

Lamoris approached the bel canto repertoire judiciously, after learning some of the earlier repertoire of Handel and Mozart, such as Donna Elvira in «Don Giovanni» and later music such as Gilda in Verdi’s «Rigoletto.» She says that when she was offered the demanding role of Lucia six years ago by three European opera houses, her first thought was «to escape from it, to go far, to refuse.»

Now she’s glad she didn’t. «I found a lot of details I never could have experienced before,» she says. «For example, different phrases, passages, coloraturas, a lot of technique which give you this pleasure to play with the music to reach the best sound of your voice, and to try to approach the perfect beauty of the human voice.»

Listing all the tools she has to express the emotion of a given moment, such as gliding portamentos, darkening or lighting up vowels, and dynamics, she adds, «Really, I enjoy it.»

articles.courant.com/2004-03-25/pittsburgh-opera-singing